Our 3-year old son, Ethan, was recently sick for six days with a very high fever. It was a difficult time! I wanted to make a record of this experience as I remember it. This is mostly for my own benefit — to have a history of a pretty scary time for us and to document how I thought through what we were observing as well as some of the decisions we made along the way. Of course, no one is as interested in others’ kids as much as the parents of those kids, so I definitely don’t expect a very wide reading of this ridiculously extensive monologue. But, if other parents happen to find themselves in a similar situation (and at least 1 in 30 kids will experience febrile seizures!), perhaps reading through our experience will be helpful in gaining both reassurance and a better understanding of the situation.

Symptoms Appear

Last Friday, as I was visiting with a friend in Harrisonville, I got a text from Meg telling me that something was going on with Ethan. He had been acting and feeling great all day, but then around 4 pm he just started to melt and she noticed that his respiratory rate was increasing. He also had a fever of 101.7 °F. This all came on very suddenly with no warning (in medical speak we would say that there was no “prodromal period” — no indicators that you are starting to get sick before you really get sick). He was totally fine until he abruptly wasn’t.

When I got home, he was indeed quite sick and in very mild respiratory distress, displaying “comfortable” tachypnea (abnormally high respiratory rate) but not displaying or progressing to any other worrisome respiratory symptoms. His fever at this point had climbed to around 103° and he was pretty miserable.

Babies and children increase their respiratory rate as a cooling mechanism, but you do want to monitor this along with heart rate, since going too far out of range, or progressing to other symptoms of respiratory distress, can indicate something serious such as pneumonia or some other type of advanced infection. Ethan’s respiratory rate was elevated but stable. He never struggled for breath and he wasn’t developing other more concerning symptoms. Pediatric respiratory distress usually occurs in a progression (illustrated here by Dr. Monica Kleinman):

- Tachypnea

- Nasal flaring

- Retractions

- Grunting

- See-saw breathing

- Head-bobbing

- Stress response

- Respiratory failure

Ethan never advanced beyond comfortable tachypnea, so I felt content with a watch-and-wait approach. We gave him lots of fluids, which he did a pretty good job drinking, at least for awhile.

His fever, however, continued to climb to over 104°.

Fever Phobia

Now, more than most people, I am pro-fever and very “non-interventionist.” So-called “fever phobia” is a huge worldwide problem (not just among parents, but even at times among healthcare professionals), and numerous papers in the medical literature have documented this over the last few decades and have tried to correct the common misconceptions about fever (see here, here, here, here, and here for a small sampling of the literature on this). Nevertheless, the fact remains that most parents are under the impression that fever is a dangerous phenomenon, with at least half of parents believing that fevers can cause brain damage or other serious complications like blindness or hearing loss.

Despite these perceptions, fever is rarely dangerous, even at quite high temperatures. It is a highly regulated internal response, such that even though endogenous pyrogens (fever-inducing chemicals/cytokines) are released, cryogens (antipyretic, or fever-reducing chemicals) are simultaneously released in a checks-and-balances fashion in order to prevent the temperature from elevating to a dangerous level. These regulatory mechanisms make it very unlikely for a fever to rise above 107.6°, and even then temperatures within the range of 104-107.6 have never been shown to be dangerous due to the fact that they are regulated by an internal hypothalamic setpoint that perfectly balances heat production with heat loss. That being said, in cases of such high fever, it would be unusual for temperatures to reach such high levels (>107°) without an overheated external environment, and you would, of course, want to investigate the reason why temperatures are so high (and always account for other concerning signs and symptoms, changes in behavior, etc.).

It is generally accepted that fever is a beneficial process that stimulates various aspects of the immune response. It also has direct antiviral effects (e.g. inhibiting viral replication). Older rodent studies demonstrated that reducing a fever could sometimes prolong an illness, and this seems to make sense given a fever’s antiviral effects (direct and indirect). However, the significance of this in humans is currently debated. Some studies show no differences in the length of illness whether the fever is treated or not, and other studies actually show that very high fevers (especially above 105°) might actually diminish immune function. On the other hand, other studies seem to show a survival advantage by allowing fevers to persist (and slightly increased mortality rates when fevers are reduced), at least in some types of infections. It really does seem to depend on the type of infection and the clinical context. If temperatures are extreme in the context of severe inflammation, sepsis, neurological injury, etc., there is sometimes a survival advantage to lowering the fever.

So this issue is not always straightforward, though generally speaking it appears that fevers are almost always harmless and sometimes helpful in resolving infections. Be that as it may, it is probably the case that reducing a fever will have only a very small effect on the length of most viral infections. The evidence for significantly prolonging an infection due to reducing fever is stronger in rodent studies than it is in human research (studies have been done but are not abundant). The question is, do the benefits of using antipyretic agents (e.g. Ibuprofen and acetaminophen) outweigh the risks of these medications? In most cases, the answer is no. These drugs are not without risks, while fevers in these instances are almost never risky. In my opinion, acetaminophen is an especially concerning drug for use in children (use of acetaminophen is associated with a higher risk of atopic diseases, and research by Schultz et al. found that children with regressive autism were nearly 21 times more likely to have used acetaminophen after the MMR vaccine than children without autism. Dr. William Shaw details many other concerns) and its efficacy for reducing fevers in children is not well-established anyway. But risks of these drugs aside, there is something to be said for comfort during a particularly uncomfortable illness, as well as concerns that might arise secondary to a high fever, like reduced fluid intake in children with resulting dehydration. In these and other situations, a case could be made for judicious use of antipyretics in order to prevent secondary complications.

Dr. A Sahib M El-Radhi, who presents a strong and meticulous case in the medical literature for fever non-interventionism, nevertheless allows for a number of situations in which antipyretic therapy could be deemed appropriate:

“Fever management may involve standard therapeutic intervention in the following situations:

• where the child has symptoms such as pain, discomfort, delirium or excessive lethargy. Antipyretics serve here to improve the child’s well-being, allowing them to take fluids, and to reduce parental anxiety.

• where there is limited energy supply or increased metabolic rate (eg, burn, cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases, prolonged febrile illness, very young age, undernourishment, and postoperative state). Fever can increase the metabolic rate and may aggravate disease.

• where young children are at risk of hypoxia because of an acute respiratory condition such as bronchiolitis. The presence of fever may increase oxygen requirements and worsen disease.

• where there is high fever of over 40°C [104°F], for the following reasons:

– Children with such high fever have rarely been studied.

– Children with such high fever are likely to be symptomatic and at high risk of dehydration and delirium.

– Not advocating antipyretics for such high fever would cause dismay among parents and controversy among paediatricians, who may consider such a recommendation unethical.”

A Trip to the ER

But back to Ethan. That night (Friday), we went to bed without treating his fever, and he eventually went to sleep. His fever was high and his breathing still tachypneic. We stayed up to monitor him since we just weren’t quite sure what was going on. We suspected it might have been the flu since we are getting into peak flu season and it’s really starting to hit our area.

Several hours later, after drifting off to sleep, we were awoken suddenly with a commotion from Ethan. Meg was already awake when and I jumped off the couch (where I had dozed off) to find Ethan in the throes of a febrile seizure. Let me tell you, even if you know what is going on, it is a truly terrifying experience to watch your child go through this!

The seizure lasted probably less than a minute, and Ethan recovered fairly quickly. Upon taking his temperature, we found that it was at least 106° (probably higher, but for some reason I didn’t let the thermometer finish). Febrile seizures are almost always harmless, and so are high fevers, but since his temperature had risen so quickly and because this was his first febrile seizure, we decided to bring him to the ER for evaluation. This is the standard recommendation for all first-time febrile seizures — not because the seizure itself is dangerous, but because the cause of the seizure might be. Sometimes (rarely) there are severe infections that need to be accounted for, and it is best to be sure nothing else serious is being missed, such as meningitis or encephalitis.

We arrived at the ER and they got us started right away. They cooled Ethan down with some damp cloths, gave him some Pedialyte (which he wouldn’t drink), and we went through the usual million-question intake process. The staff was great and very friendly, and they respected and even asked for some sincere dialogue on some of our unconventional medical views (e.g. our vaccination decisions) even though they didn’t agree with us.

They wanted to give antipyretics and antibiotics, but I refused. We were all (emergency room personnel included) pretty well convinced that this was a viral infection, so I didn’t want to give antibiotics based on the very small possibility that this was a bacterial infection. I also didn’t want to necessarily give antipyretics at this point. The fever had come down since we’d been there and was running around 102. I (rhetorically) asked the doctor if Ethan was in danger from the fever. He said he wasn’t. I explained that I had some concerns about Tylenol, in particular, and would rather not use it if I didn’t have to. It was apparent that he thought this was nothing short of a little bit ridiculous, but he was nice about it and went along with my wishes. He did recommend some testing (e.g. CBC, CMP, bacterial cultures, influenza and strep tests, etc.), which I agreed to. It’s a good idea to gather some information like this after a first-time febrile seizure.

The influenza test and rapid strep test came back negative, and the other labs showed evidence of infection but were otherwise unconcerning. Some of the electrolytes were out of range, and they really should have given IV fluids but they didn’t. Interestingly, alkaline phosphatase was quite elevated. This is often seen in viral infections. It is most commonly elevated in enterovirus infections but has also been noted in association with other viruses like HHV-6. This was somewhat reassuring to me that we were indeed dealing with some kind of virus.

Febrile Seizures

Febrile seizures, which occur in at least 2-5% of children between the ages of 6 months and 6 years, are by definition seizures that occur with a fever. They’ve been recognized for millennia. Even Hippocrates (460-377 BC) described them over 2,000 years ago:

“Convulsions occur to children if acute fever be present…most readily to children which are very young up to their seventh year. Older children and adults are not equally liable to be seized with convulsions in fevers unless some of the strongest and worst symptoms precede…”

While febrile seizure susceptibility has a strong genetic component, they are also overwhelmingly associated with viral infections, the most common ones being rhinovirus, adenovirus, enterovirus, influenza, and HHV-6. Some evidence seems to suggest that it isn’t so much the absolute temperature of the fever, but rather the speed of the temperature rise (though this is debated) that brings on the seizure. The seizures can occur with both high and low fevers, and the viruses themselves contribute due to the fact that many actually replicate within the central nervous system (CNS), which increases seizure potential.

Febrile seizures can be “simple,” “complex,” or “febrile status epilepticus.” The simple seizures last for less than 15 minutes (often a minute or less), while complex seizures last for longer than 15 minutes or there are multiple episodes within 24 hours. Simple seizures generally involve convulsions of the whole body (i.e. no focal features), while complex seizures can have focal/isolated features. Febrile status epilepticus is a febrile seizure that lasts more than 30 minutes.

Ethan’s seizure was a simple seizure, as it lasted for well under 15 minutes and was a generalized tonic-clonic (grand mal) seizure.

Once we had all of the labs back and verified that nothing else seemed concerning, we went home. We took the Pedialyte with us and tried to get more fluids into him, but he just wasn’t interested in drinking. He still had a fever but seemed comfortable enough and looked good, so we went to bed and he was able to go to sleep.

The Second Seizure – A frightening experience

To our dismay, a few hours later we woke up again to Ethan having another seizure! This one was different from the first. It seemed to keep going and going. The convulsions lasted at least 10 minutes — maybe more. I was caught up in the moment and forgot to look at the clock exactly when it started, but I think it was around 8:10 am. I rolled him onto his side and let the seizure run its course. Basic first-aid like this is necessary to make sure the airway stays clear. He did vomit a bit during this seizure (not uncommon), so being on his side was a good thing, but there is no need to otherwise restrain the convulsions or interfere in other ways. It’s best to try to remain calm and let the seizure play itself out. Eventually, the generalized convulsions started calming down but focal features remained, and he didn’t start loosening up some of his rigid muscles (like one of his arms and his feet) for at least 20 minutes. Even then, he didn’t snap back like he did the first time. He just laid there with a distant look in his eyes, repeating an “uh-uh-uh-uh” sound over and over and over. He was not unconscious and his vital signs were great, but he would not communicate. Sometimes he would follow a movement with his eyes, but he wouldn’t talk or attempt to communicate in any other way.

Of course, this was VERY SCARY STUFF for us as his parents. I’m no pediatrician and don’t even remotely pretend to be one. I had brushed up on my knowledge of febrile seizures before all this started (thankfully!), but I’m certainly no expert and I know my limits. Was this normal? Obviously, this was a complex febrile seizure, but how long can it take to get back to normal awareness and communication after a pretty intense complex seizure like this?

I called the ER and explained the situation. They thought it was probably okay, but that I should bring him back in if he continued to act this way once we reduced the fever or if he got worse. High fevers can be disorienting and maybe that’s all it was. I didn’t feel much better about it, but said “okay.” We quickly brought down his fever with some damp cloths (which we had already been doing) and then continued to observe, hoping and praying for the smallest word or even just a look of comprehension. Just a “hi” or a “fine” or something other than this distant stare with strange, repetitive sounds. He was just so different. I “knew” that febrile seizures are almost always harmless, but you just keep thinking, “What if this is that exception to the rule?” He just seemed so neurologically altered. Like when you see before-and-after footage of kids with regressive autism or before-and-after vaccine injuries. It’s like you’re looking at a different kid. All of these things flash through your mind due to the unknown. Is our life changed forever? Will he ever talk again? Will he ever say to me again, “Daddy, come play with me!” (like he does at least a dozen times, every single day)? These and a hundred other things are spinning through my head, even though I know that this sort of damage is extremely unlikely and is only found in the rarest of case reports in the medical literature. Still, how do I account for the odd post-seizure behavior I’m witnessing?

I’m so thankful for my mom at this point, who had the clarity of mind to suggest that I call Children’s Mercy Hospital to talk to their nurse hotline. I had already called the local ER again but felt like I needed a more specialized opinion, and hopefully this would be helpful. I called the hotline and talked to one of the nurses. What I was hoping she would say was: “Oh, yes. That can be very normal with complex febrile seizures. Just give him a little more time and he’ll bounce right back.” But she didn’t. She explained that she was “very concerned” with my description, as Ethan’s recovery was taking too long and she did not like that he was still being so unresponsive and uncommunicative. “Something has happened to him,” she said. “And he needs to be reevaluated as soon as possible.” (Talk about making your stomach drop.) I asked if she thought he had sustained some kind of neurological damage. She replied, “Not necessarily… but I think they [the ER] have missed something.” She instructed me to tell the ER to call Children’s Mercy and they would consult with them on Ethan’s case.

Back to the Hospital

So we jumped back in the car and we rushed back to the hospital. At this point, my nerves were really on edge (and I probably drove faster than I should have). But we arrived safely and brought Ethan back in. The staff had turned over from the night before, but they all knew who we were (small town, and I had called them twice that morning already). Again, they got us right in, and I explained again about Ethan and about Children’s Mercy and how they needed to consult with them. They said “Okay” without any argument and got Ethan into a room. They administered antipyretics (which I didn’t refuse this time!). I don’t know what Children’s Mercy told them, but they ended up running a bunch of other labs that they hadn’t run the first time. They also ordered (but never performed — see below) a CT scan of his head.

Then we hit a turning point. They hooked Ethan up to IV fluids. Almost right away, you could see him starting to change. His color and complexion started to look more normal (even though we hadn’t realized he looked different until he started changing back. It must have been so gradual we missed it). Then he started to get upset about something the nurses were doing (a good sign), and it sounded like he tried to say something — though it just came out as unintelligible mumbling noises. Still, it was better than the “uh-uh-uh-uh” sounds that had never really stopped since the end of the last seizure and had continued now for hours. A little more time passed and he said “no!” in response to somebody’s question and then “ouch!” when they drew some blood. Our nurse, Kerri, said, “You’re okay!” And Ethan said, “No, me NOT!” And Meg and I cried tears of relief. Our boy was back.

So the nurse at Children’s Mercy was right — they had missed something. I believe that Ethan was mildly dehydrated the first time we brought him in and should have had IV fluids at that time with electrolyte repletion. Looking at his labs, which the hospital supplied to me, his sodium and chloride levels were low (though potassium and magnesium were great). Sodium was below the reference range by six points. What are some symptoms of low sodium (hyponatremia)? Mental confusion, lethargy, malaise, cramps, seizures… His level was 130, which qualifies as only “mild” hyponatremia (the normal range is 136-145), and some of these symptoms don’t really manifest until much lower levels (<120-125). But his level was likely still significant as a contributing factor, especially in the context of the illness he was fighting. There was certainly no doubt that he needed fluids once we saw the almost immediate and dramatic change in his speech and behavior! The thing is, he had not exhibited classic signs and symptoms of dehydration. But I think it worsened quickly after getting home from the hospital the first time. As the fever came back up, he definitely stopped drinking as much, and this was subtle enough that we hadn't really noticed except in hindsight. We stayed at the hospital all morning, and he kept improving as more time passed. All the various labs came back (except for bacterial cultures, which take a couple days) and they were all normal enough to rule out anything serious. The doctor was so pleased with Ethan's improvement at this point that he decided to call off the CT scan. This was enormously relieving, as I had not wanted Ethan to be exposed to so much radiation. When we first brought him in it appeared to be justified, however, given the severity of his presentation.

They ended up giving Ethan one more round of IV fluids, and when that was done we were ready to go home. We were instructed to treat the fever “aggressively” with ibuprofen every 6 hours, using acetaminophen between doses as needed.

Back Home and Staying Hydrated

Ethan was now his old self. The antipyretics they had given at the hospital made him feel great (no fever) and he wanted to play, play, play! It was so good to see him acting normally. We pushed the fluids at every opportunity. Water, Pedialyte, popsicles, homemade snowcones, etc. Anything to get the fluids in. He loved the Pedialyte for about the first 5 minutes, and then he refused it and would never drink it again. Odd, but oh well.

Oral Rehydration Solutions (ORS)

As an alternative, I made up a basic homemade oral rehydration solution (ORS). ORS formulas are used worldwide as alternatives to IV fluids in cases of mild to moderate dehydration, and reduce the death rate from diarrhea-induced dehydration (e.g. cholera) by a whopping 93%. The best and most current evidence-based formula (via WHO guidelines) is as follows:

Per liter of water:

Sodium Chloride: 2.6 grams

Potassium Chloride: 1.5 grams

Glucose (Dextrose): 13.5 grams

Trisodium Citrate: 2.9 grams

This is known as the WHO-ORS. Of course, not everyone has access to all of these ingredients or the tools (such as a gram scale) to make up an accurate ORS. The above ORS is not usually prepared at home but is provided in pre-prepared packets.

In a pinch, one can throw together a very basic ORS as follows:

Per liter of water:

Sugar (6 level teaspoons, or 25.2 grams)

Salt (1/2 teaspoon, or 2.9 grams)

This is not optimal but it does save lives in cases of dehydration when no other options are available.

Pedialyte (and Gatorade, too) is basically just a commercial ORS, though the electrolyte composition is slightly different than the WHO-ORS and randomized trials suggest that the WHO-ORS has greater satisfaction and effectiveness rates than Pedialyte.

Note: While Gatorade is relatively effective as a rehydration solution, it is not an effective solution for reversing low potassium levels (hypokalemia), unlike the WHO-ORS and Pedialyte, which contain over 6x more potassium per liter.

Ethan had just been loaded up on IV fluids at the ER and he didn’t have diarrhea, so he wasn’t really in danger of dehydration as long as we could keep the fluids up in general. He actually loves his water to be “flavored” with vitamin C (it makes it kind of sour/tangy), so I mixed him some vitamin C water with honey, salt, and some stevia to make it a little sweeter without going higher than needed on the sugar. When making a ORS, you don’t want to omit sugar since the absorption of sodium requires glucose via the SGLT symporters in the gut. (Note: if you’re not acclimated to vitamin C it’s best to omit high doses since that could cause diarrhea and thus worsen dehydration.)

ORSs are really geared toward treating diarrhea-induced dehydration, and it might have been a little bit overkill in this situation to push it at every opportunity, but since he had previously had a low sodium level and was also resistant to drinking during fever (and wouldn’t drink Pedialyte), I wanted to play it safe and make sure he was getting enough fluids and sodium into his system when we had the opportunity and he did feel like drinking.

The Antipyretic Predicament

The antipyretics eventually wore off, of course, and the fever started coming back up. Ethan’s symptoms were mostly limited to the high fever. He occasionally complained of various things hurting (especially his stomach whenever his fever started spiking), but the main thing was the fever and the discomfort that it caused. Whenever the fever was reduced there were no other symptoms and his behavior and symptoms were completely normal.

We didn’t want to use the ibuprofen, but we also didn’t want to go through another seizure, especially if there was even a possibility that it would result in such a long and psychologically-disturbing recovery period like the last time. Since fever is obviously a trigger for febrile seizures, it seems to make intuitive sense that treating the fever should prevent the seizure. That was the impression we got from the ER staff, and I had no reason to doubt this at the time.

We were also a little more open to considering the use of antipyretics due to the fact that Ethan tended to stop drinking once he got up to a high temperature, and this is what resulted in him getting dehydrated previously.

So while I understood that there were risks to using ibuprofen (we normally don’t even have any antipyretics in the house except for some aspirin, and haven’t for years), I felt as though the risks of dehydration were greater, and decided to give the ibuprofen as needed.

So the rationale was:

- Keep the fever down to prevent more seizures. No, the seizures are not dangerous, but they are frightening to watch, and the last atypical seizure experience left us especially disinclined to go through another one!

- Keep the fever down to prevent dehydration.

Homeopathy Helpful but Incomplete

We did try to minimize the ibuprofen as much as possible. We were able to spread out its use at times by using damp tepid cloths around the lower legs (“calf packing,” which he hated) and also got quite a bit of mileage out of homeopathy. Pulsatilla 200C was at times almost shockingly effective, lowering the temperature by at least a couple degrees within 5-10 minutes on several occasions. We also tried Bryonia, Aconitum, and Rhus Tox at various times and in various combinations. We did not have the classic high fever remedy, Belladonna (in any potency), and couldn’t get it locally. Most of these remedies had little effect other than the Pulsatilla, but even that was inconsistent, and eventually we ran out anyway.

While I am not a homeopath, when I do use homeopathy these days I tend to follow the “Banerji Protocols,” which diverge in significant ways from classical homeopathy. There are a couple of Banerji protocols that might have been applicable, here. For generalized fever, the protocol is Eupatorium 30C together with Belladonna 3C. For high fever with convulsions, the protocol is Arnica montana 3C together with Cuprum metallicum 6C every 10-15 minutes. I didn’t have any of these remedies/potencies on hand. My mom was able to find the Eupatorium 30C and some Belladonna 6C locally, and she brought these to us toward the end of this illness. It wasn’t a dead match (Belladonna 6C instead of 3C), which seems to be fairly important in the Banerji protocols, but I was hoping it was close enough. Unfortunately, it didn’t seem to have much effect. I would have liked to see what the correct potencies could have done in this situation.

These were wicked fevers, and sometimes they would spike really quickly, especially at night. Untreated, the fevers were always above 104°, and usually in the 105° range or higher. On Tuesday it jumped up to 106.7°, which, even if you’re not generally a fever-phobic type of person, can seem kind of scary. We did reduce the really high fevers with antipyretics when other methods didn’t work. He was miserable at these high temperatures.

Antipyretics Don’t Prevent Febrile Seizures?

Now at this point, it would be interesting to point out some of my findings regarding febrile seizures and antipyretic therapy. Recall that we were instructed to aggressively treat the fever in order to prevent more seizures. This came from the ER staff as well as the handout sheet on febrile seizures they sent us home with, which commanded the use of continuous antipyretic therapy (complete with instructions to wake the child in the night to administer the medication). This advice seems so obviously correct that it hardly seems worth a second thought. If fevers trigger these seizures, then surely fever-reducing therapy should prevent seizure recurrence…right?

It turns out that that might not be the case. This seems ridiculously counterintuitive, but all of the most recent evidence seems to suggest that antipyretics are ineffective at preventing febrile seizures!

According to the British Medical Journal, the bottom line is that antipyretics “following febrile seizures may provide comfort and symptomatic relief, but should not be recommended to prevent further febrile convulsions.”

And a massive (117 page) 2017 Cochrane Review of 30 randomized trials including over 4,200 children found no significant benefit from antipyretic therapy. The authors concluded:

“Neither continuous nor intermittent treatment with zinc, antiepileptic or antipyretic drugs can be recommended for children with febrile seizures. Febrile seizures can be frightening to witness. Parents and families should be supported with adequate contact details of medical services and information on recurrence, first aid management and, most importantly, the benign nature of the phenomenon.” (Prophylactic drug management for febrile seizures in children.)

Medical literature from over 10 years ago makes the claim that “Antipyretics are effective in reducing the risk of febrile seizures if given early in the illness.” This seems to make great sense since the seizures tend to occur early on in the febrile illness (often on the first day). But no documentation is provided for this statement. It seems like common sense, and perhaps it is true. But the overall weight of the evidence as of 2017 doesn’t seem to support it unless the published research has overall failed to make distinctions in the timing of the administration (“early in the illness” vs later) or some other subtle nuance. Again, these findings are counterintuitive and I certainly have a difficult time comprehending that antipyretics could be ineffective at preventing seizures if they are indeed mitigating the fever down to normal temperatures. I don’t pretend to understand what’s going on with that.

In any case, once I learned about the probable ineffectiveness of antipyretics for preventing another seizure (even by the old standards, we were no longer in the “early” stages of the illness), I felt as though I still had sufficient justification to keep reducing the fever any time it got high enough that 1) the discomfort was obviously intolerable, and/or 2) fluid intake slowed or stopped. If those two factors had been absent and Ethan had a high fever without extreme discomfort or risk of dehydration, I don’t believe I would have treated the fever.

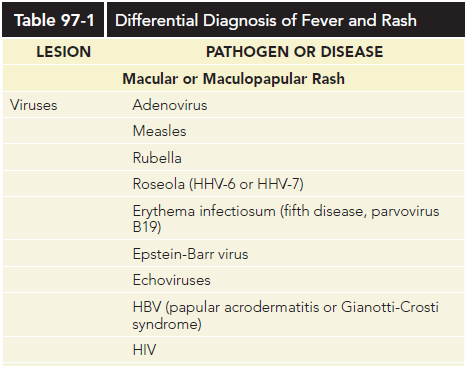

The Viral Short List

What kind of virus was this? The best fit seemed to be HHV-6B (human herpesvirus 6B), the nearly ubiquitous virus that causes roseola in kids (HHV-7 is also possible but less likely). Roseola is characterized by a sudden high fever with no prodromal period and few other symptoms. The fever can be intermittent and usually settles into the elevated range of 104-106°F. It’s sometimes referred to as the “three-day fever,” as it often lasts for around three days, but can actually last anywhere between 3-7 days. Roseola/HHV-6B also frequently results in febrile seizures. The fact that Ethan had a complex febrile seizure (instead of just a simple seizure) also makes HHV-6 a far more likely candidate, as HHV-6 can be identified at least 42% of the time in those presenting with complex febrile seizures — a frequency far surpassing any other single virus. After the fever is gone — usually within 2-3 days (but sometimes during the defervescent period) — a light pink to red rash may appear on the trunk and spread peripherally to the arms, legs, and neck. The rash can be macular or maculopapular (flat or flat with bumps). Interestingly, HHV-6 can occur without a rash at all. In fact, while the vast majority of children are infected with HHV-6, only a minority develop the clinical features of roseola, and many have no symptoms at all. This can be very frustrating, as it leaves parents wondering what they just went through. If it wasn’t roseola (no rash?), does this mean we have to go through another super-high-fever illness like this again in the future?

Another strong candidate would be some kind of enterovirus. Over 90% of enterovirus infections result in nonspecific febrile illness with sudden high temperatures. These fevers can last a week and can show a biphasic pattern. Temperatures are typically 101-104°F, and respiratory and gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal discomfort, etc.) might also be experienced, depending on which enterovirus you’re dealing with. Enteroviruses are also detected very frequently in febrile seizure cases. Ethan’s symptoms might fit with an enterovirus (viruses don’t always present as textbook examples), and his elevated alkaline phosphatase level could also be consistent with this, but it just doesn’t seem quite right in several other ways, and overall, HHV-6 is a much closer fit in pretty much every way. His fever was much higher than what you typically see with an enterovirus, the pattern was more intermittent than biphasic, and there were few other accompanying symptoms (with the exception of abdominal pain during fever, which would be consistent with enterovirus, but not exclusively). The complex seizure also increased the likelihood of HHV-6 over other types of viruses.

For the sake of completeness, I should also mention adenovirus, which was on the list of common febrile seizure-inducing viruses. This is also a possibility, as adenovirus is known for prolonged high fevers. While adenovirus can vary pretty widely in its presentation (depending on serotype), Ethan’s illness was in most ways (except the high and prolonged fever with seizures) inconsistent with almost every typical adenovirus serotype presentation.

Improvements! (And finally some herbal remedies to the rescue)

It was the second day of the fever when I started suspecting roseola, and even brought it up to the ER nurse, who agreed that this seemed likely. So we crossed our fingers and hoped for a quick resolution on day 3, which would be a “typical” length for roseola. Nope. It kept dragging on and eventually lasted six days.

Toward the end of this time, my wonderful mother again helped us out. She decided to make a special trip to the health food store to see if they had some of the herbal remedies that I was wishing I had.

As a naturopathic doctor, you would think I would be well-supplied with all manner of vitamins, herbs, and other various remedies. But in actuality, I keep very little in-office inventory (I have most of my clients’ remedies drop shipped from a nutraceutical dispensary and don’t really deal with acute situations) and was caught completely off-guard by this illness. If I had known it would last almost a whole week I would have ordered some things, but I kept thinking it would probably be over in a couple days before an order would even arrive or be of any use.

I requested a few basic remedies with the assumption that this was probably HHV-6 (an enveloped virus) but also wanted something broad-spectrum enough to cover enteroviruses as well (which are nonenveloped viruses). I chose Sambucol syrup (black elderberry), lemon balm tincture, and licorice tincture. All three are very active against the herpesviridae family of viruses, but also have antiviral effects against enteroviruses. Licorice is one of the most potent (and frequently underappreciated) antiviral herbs, and lemon balm really shines when it comes to the herpes viruses, in particular. Lemon balm has nervine (calming) properties, which can help a fussy kid relax and get some rest during an uncomfortable time. Lemon balm is also a diaphoretic (sweat-inducing), and can thus help to cool down a fever.

My mom arrived with the remedies in the afternoon and we started giving them to Ethan right away. I mixed 10 mL of Sambucol syrup with 1 mL each of the licorice and lemon balm tinctures. The nice thing about this combination of herbs is that they all taste great together. Ethan drank it down with very little problem, and we ended up giving three doses of this by the end of the evening, including a dose right before bed.

This time as Ethan went to sleep, he broke out in a sweat and his temperature dropped to about 96.6°. We checked up on him throughout the night and his temperature stayed almost exactly the same and he slept more soundly than he had slept all week. I was sure that this was the end of it. Close, but not quite.

At about 4:00 am, he started getting restless and his temperature started coming up again. He got another dose of the elderberry/licorice/lemon balm and fell back asleep. His temperature continued to rise, but this time it didn’t get higher than about 104.5° — a low temperature for this illness! Also unique was the fact that he was sleeping very comfortably, despite the fever. Since he was comfortable and his temperature was stable, we chose not to use any antipyretics and just let the fever run its course. He slept for at least a few more hours while the fever continued, and then suddenly the temperature started dropping. Down, down, down…normal. No dramatic “breaking” of the fever like you often see with febrile illnesses. Just a gradual decrease and then it was gone.

Ethan woke up feeling great. More herbs for good measure and the day continued without any more fevers. They never did come back.

UPDATE: Approximately three days after the end of the fever, Ethan did present with a light, macular rash on the trunk, neck, and arms. This was extremely short-lived — perhaps no more than half an hour. It could have been the roseola rash, which is at times very slight and very short-lived, but we will never know for sure! It appeared suddenly on his back, spread to his neck and arms, and then began to fade almost as soon as it showed up.

UPDATE: Approximately three days after the end of the fever, Ethan did present with a light, macular rash on the trunk, neck, and arms. This was extremely short-lived — perhaps no more than half an hour. It could have been the roseola rash, which is at times very slight and very short-lived, but we will never know for sure! It appeared suddenly on his back, spread to his neck and arms, and then began to fade almost as soon as it showed up.

Closing Thoughts and Speculations on Seizure Prevention, Herbs, and the Benefits of Childhood Infections

Was it the herbs that made a difference, or would he have followed this same course regardless? We’ll never know for sure, but after observing the patterns of this illness for a week, I feel like they noticeably interrupted that pattern and seemed to make a big difference in overall comfort, temperature, relaxation, temperament, sleep, and possibly the duration of the illness. I wish I would have had these items from the start.

Ideally, I would have liked to add in a couple other things, such as chamomile and catnip, which might have further attenuated the high temperatures and aided in reducing the discomfort.

In a perfect world, I would have also liked to have Chinese skullcap and Isatis on hand — both are potent antivirals and synergistic with licorice in particular. Both are very broad-spectrum and active against a wide range of enveloped and non-enveloped viruses alike. Both are bitter, and Isatis can be especially awful, so they need to be used in combination with something sweet like licorice (which is preferable anyway from a synergistic efficacy standpoint) to offset the flavor. Even then I’m not sure how well it would go down. It can be hard enough to get a 3-year old to take dose after dose of any kind of medicine, especially when they feel terrible.

If this was HHV-6, could it have been prevented? Probably not. This virus is nearly ubiquitous in children (most are actually infected by age 2).

[And as a sidenote: Moms and dads, try not to concern yourself with trying to figure out where your child caught the virus from, and certainly don’t place blame on anyone for spreading the virus to your family. Again, almost all children are eventually and inevitably infected, and in all likelihood, they got it from you! Asymptomatic adults (who are pretty much all previously infected) periodically shed the virus and this is what usually ends up infecting the kids. The reason infection doesn’t usually show up until at least 6 months is because infants are protected from infection by transplacental antibodies. Once these maternal antibodies start declining, the incidence of infection increases.]

Plus, I’m not entirely sure you would want to prevent infection even if you could. Many of these childhood viral infections appear to have longterm benefits. Take chickenpox, for example, perhaps the most notorious of the childhood herpesviruses (HHV-3). Those with a history of infection tend to have a lower risk of various cancers (including brain cancer) later in life. In fact, most of the classic febrile infections of childhood (measles, mumps, rubella, pertussis, scarlet fever, and chickenpox) are associated with a lower risk of many types of cancer in adulthood. This likely extends far beyond cancer. Measles and mumps infections are associated with a lower risk of dying from heart disease later in life. From a naturopathic perspective, our efforts should be geared more towards reducing the severity and duration of these infections rather than all-out avoidance or prevention in most cases, since many of these infections are benign in the healthy child. There are other considerations that go beyond the scope of this discussion, of course, such as the fact that reactivation of various viruses and/or increased viral titers are implicated in various adult disease states (e.g. multiple sclerosis), but overall and for the most part it appears as though childhood infection is normal and even desirable.

Another pondering thought is this: Would prophylactic treatment with CBD oil (cannabidiol) have any value in preventing febrile seizures in at-risk children? To my knowledge, this has not been studied (though the endocannabinoid system has been touched on in the febrile seizure literature, exogenous cannabinoids have not been explored), but it is a plausible hypothesis given the established value of CBD in other seizure conditions. In the young brain, glutamate decarboxylase (an enzyme responsible for the conversion of glutamate into GABA) is inhibited by heat. This leads to a buildup of glutamate (a primary excitatory neurotransmitter) and a deficiency of GABA (the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter), which can play a role in the onset of febrile seizures.

CBD modulates glutamate signaling, inhibits glutamate release, and potently reduces glutamate toxicity. And when mice are pretreated with CBD, tonic seizures are able to be prevented, and this appears to be due to CBDs effects on GABA-related mechanisms.

CBD has numerous other anticonvulsant actions apart from its effects on glutamate and GABA, and holds promise for a wide variety of seizure conditions.

CBD is non-psychoactive and has been studied in young children, but the literature on this is not extensive. Due to its inhibitory action on cytochrome P450 enzymes, it might not be a benign choice if there are other medications in the mix that might result in drug-herb interactions.

CBD is poorly absorbed orally (~6%), and if I were to use it, I would select an enhanced-absorption formula so that the dose could be kept relatively low while still achieving high and sustained blood levels. Quicksilver Scientific’s Colorado Hemp Oil is a nanoemulsified CBD product that I use for other applications (e.g. neuroinflammation), and it has been shown to have excellent bioavailability and achieve high blood levels with low dosing. Would treating an at-risk child at the very beginning of a febrile illness with a CBD formula like this prevent the onset of a febrile seizure? I don’t think anyone knows at this point, and we would need randomized trials to answer the question, but the idea seems credible! In the research on febrile seizure prophylaxis, the only medications that seemed to have any efficacy for preventing recurrent seizures were antiepileptic and benzodiazepine medications like phenobarbital and diazepam. But the number needed to treat (NNT) was so high (16 children would need to be treated for up to two years to prevent one seizure) and the side-effects were so frequent (adverse effects in a third of treated children) that these are not appropriate or recommendable options. Since CBD has at times been shown to meet or exceed the efficacy of antiepileptic/anticonvulsant medications without inducing the same adverse effects, it would seem to be a promising (though untested) alternative.

There is one additional caveat to using CBD in this situation. Due to cannabinoids’ anti-inflammatory effects, some research posits that the immune system’s antiviral response might be inhibited by cannabinoids, leading to disease prolongation in acute infections. However, I would be surprised if this was any more significant than the anti-inflammatory effects produced by antipyretic medications (e.g. ibuprofen), and we know that these medications do not generally lead to a significant prolongation of viral illness in humans (depending on the context and nature of the infection). Also, it’s worth noting that newer research finds both benefits and drawbacks to using cannabinoids in the context of viral infections. It might be a double-edged sword, depending on which virus, and whether it’s acute or chronic. For a minor viral infection, it’s a judgment call, just like the use of antipyretics. A minor (and probably insignificant) suppression of antiviral defenses might be a worthy tradeoff for the potential to prevent a febrile seizure.

Recent Comments